Verdict in the Network case: where the impossible is the norm

Seven people have been convicted by a military court in Penza in a case involving fabrication of evidence and torture. What does this mean, and how did we come to this?

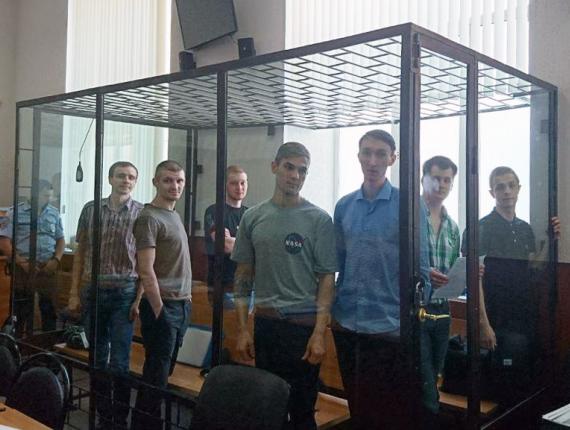

On 10 February 2020 the verdict in the so-called ‘Network’ case was announced: seven young men, supporters of anarchist and anti-fascist ideas, were sentenced to terms in prison colonies ranging from six to 18 years for creating, or participating in, a terrorist group, and also for possessing weapons and ammunition.

The charges, and subsequently the verdict, were built on confessions the court should have rejected, not least because they were obtained by torture. Some of the defendants in the case were tortured after they had been detained, but before that detention had been formally recorded, during a time when they temporarily ‘disappeared’ from the purview of the law. The torture then continued until the defendants had given testimony that aligned with the charges fabricated previously. The Network group, evidently, was a paper creation, based on the materials of an ‘operational report’ about left wing activists. Subsequently, individuals who knew each other but little or not at all were forced to admit to participation in a single ‘terrorist organisation.’

‘Participants’ in this organisation were not charged with the commission of any actions, nor with having developed specific plans, but only with indefinite intentions, with having ‘planned’ something criminal ‘in a place and at a time that have not been established, in circumstances that have not been established by the investigation, jointly with persons who have not been identified, guided by the ideology of anarchism,’ It is claimed that Network had a charter and held congresses. The investigators gave the title ‘congresses’ to various open meetings, including ordinary social gatherings at which one or other of those convicted was present or accidentally met with another (after all, most of the members of Network did not even know each other). As experts have shown, the ‘charter’ of the group of anarchists (a thing which would in itself be amusing!) appeared on a computer after it had been seized, when the owner was already held on remand, and was then edited by unidentified persons. No fingerprints or other biological samples of the defendants were found anywhere on a meagre store of arms, including on the weapons and ammunition, that allegedly were discovered. Investigators, for their part, did not even try to establish the circumstances in which the weapons had been acquired. Pressure was applied not only to the defendants, but also to witnesses, many of whom complained about this and rejected testimony they had at first given. This weak ‘evidential base’ was strengthened by the testimony of ‘secret witnesses.’

During the trial it became evident that the Network organisation, that has been designated as ‘terrorist’ and banned in Russia, did not in fact exist.

The Memorial Human Rights Centre has already recognised the defendants in the Network case as political prisoners (see the materials about the Penza and St. Petersburg prosecutions on our website).

***

The verdict in the Network case is already being called ‘unprecedented.’ However, there have been more than enough examples of similar sentences over the last twenty years.

From the very beginning of the ‘counter-terrorist operation’ in the North Caucasus, Russian federal military, law enforcement and security services made wide use of abductions, unlawful detentions and cruel torture, both against those suspected of ‘terrorism’ and against those who clearly had no connection to such crimes.

In recent years this practice has been extended to other Russian regions and to other categories of cases, and has been far from limited to cases related to ‘Islamic extremism.’

For example, Ukrainians Mykola Karpyuk and Stanyslav Klykh, under horrific torture during the investigation, admitted to all the charges fabricated against them of having allegedly participated in events of the First Chechen War. The judicial motivation for the conviction was a nonsense. But this did not hinder the sentencing of the two in 2016 to 20 and 22 years in prison colonies, respectively.

Fifteen people, who were sentenced in 2016 to jail terms of up to 13 years for allegedly preparing a terrorist attack on the Kirghizia cinema in Moscow, had in common only the fact that they were builders, most of whom did not know each other, but who had at various times rented a sleeping place in the same hostel. They confessed under torture to taking part in a ‘terrorist cell.’

Memorial has recognised those convicted in these cases as political prisoners. The list can be continued.

***

The use of torture and fabricated evidence in the Network case were known from the very beginning, in the winter of 2018. The St. Petersburg Public Oversight Commission was able to record marks of torture to which the suspects had testified. However, neither wide publicity nor appeals to the law enforcement agencies prevented the fabrication of the charges or the convictions. The case is worthy of the Stalin era in terms of its absurdity and lack of evidence for the charges, the methods of obtaining confessions and the severity of the sentences. However, it was developed and brought to a conclusion by investigators, prosecutors and the court not in secret, not in some deep dungeon, but, essentially, in full view of the public, in the spotlight.

Читать заявление на русском языке