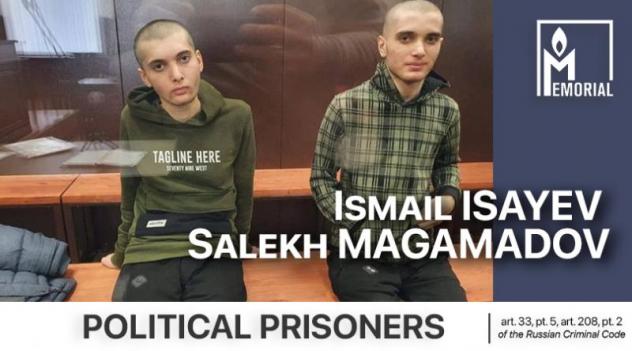

Brothers Ismail Isayev and Salekh Magamadov are political prisoners

Two young Chechens who criticized the authorities on the Internet were abducted and forced to publicly repent. After leaving Chechnya, they were detained in Nizhny Novgorod on charges of aiding and abetting militants

Memorial Human Rights Centre, in accordance with international guidelines, considers the criminal case against Ismail Isayev and Salekh Magamadov politically motivated and unlawful. Their prosecution has been intended to force them to end their public criticism of the authorities and is based on their belonging to the Chechen LGBT community. The prosecution of Isayev and Magamadov violates their rights to freedom of expression and to liberty and security of person.

- The case against Isaev and Magamadov

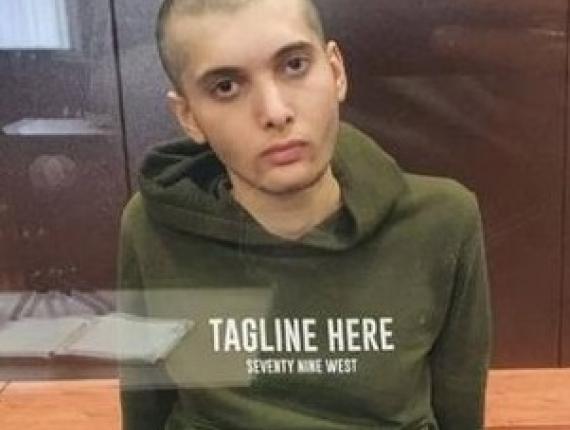

Ismail Isayev and Salekh Magamadov are brothers who are 18 and 20 years old respectively. Isaev has taken the surname of his father, Magamadov the surname of his mother. One of the young men is gay, the other is undergoing gender transition.

In April 2020, pro-government Chechen Telegram channels and Instagram accounts distributed videos in which a group of very young people (eight young men and one young woman) who were participants in a Telegram chatroom entitled ‘Osal nakh 95’ (Chechen for ‘Unprincipled People’), apologized for ‘doing bad unprincipled things,’ in other words, criticizing the authorities, public officials and Islam. Two of the people on the tape turned out to be the brothers Ismail Isayev and Salekh Magamadov.

According to Isayev and Magamadov and their relatives, the brothers were forced to repent by their captors. Isayev was abducted in St. Petersburg and Magamadov in Grozny. They were kept for almost two months in Grozny at the headquarters of the traffic patrol regiment named after Akhmat Kadyrov along with 27 other prisoners. During that time they were systematically beaten, humiliated and intimidated, forced to recognize the existence of God and to learn by heart passages from the Koran, the biography of Akhmat-Khadzhi Kadyrov and the national anthems of Chechnya and the Russian Federation. According to the two young men, their abductors justified this treatment not only on the grounds of the brothers’ participation in the Telegram chatroom but also because of their sexual orientation which needed to be ‘corrected.’

Isayev and Magamadov were released at the end of May 2020.

In July 2020, with the support of lawyers from Sfera, a social and legal aid foundation, the parents of the two men took them from Grozny to Nizhny Novgorod where they lived while they waited for an opportunity to leave Russia.

On 4 February 2021, Chechen law enforcement officers detained the brothers in a Nizhny Novgorod apartment and took them to Gudermes in Chechnya.

In Chechnya, in the absence of their lawyers who had been denied access to Isayev and Magamadov, the brothers were charged with aiding and abetting participation in an illegal armed group (Article 33, Part 5, and Article 208, Part 2, of the Russian Criminal Code). The brothers were threatened and forced to sign confessions. According to the authorities, in June 2020, while waiting in their parents’ Grozny house for assistance from lawyers and an opportunity to leave Chechnya, the brothers made the acquaintance via the Internet of the militant Rustam Borchashvili, who is on a wanted list, and on two occasions they took food to him in the forest 50 kilometres from Grozny.

The brothers’ representatives lodged an application with the European Court of Human Rights, which on 8 February ordered interim measures under Rule 39 of the Rules of the Court. The Court demanded the Russian authorities order an immediate medical examination of the detainees and ensure their lawyers and close relatives had access to them. The Court also requested information from the Russian authorities as to the steps taken with regard to the brothers' allegations of abduction and torture.

Ismail Isayev and Salekh Magamadov are currently being held in a remand centre from where they also report being subjected to constant beatings and threats.

- Isayev and Magamadov are political prisoners

The case of Isayev and Magamadov is replete with gross violations: lawyers were not allowed to see them, deadlines in the proceedings established by law were violated, the brothers and their parents were subjected to pressure and tortured.

The evidence of the brothers’ guilt in the indictment appears unreliable, insufficient and raises suspicions of fabrication. For example, the investigators’ description of ‘becoming acquainted with a militant via Facebook’ is replete with ambiguities and technical errors and the testimony of two taxi driver witnesses who identified the brothers is repeated verbatim.

The dates of the imputed actions are questionable. According to their mother, the young men spent all June at home in Grozny, waiting for an opportunity to leave Russia. The investigators’ version of events, according to which the young atheists, who belonged to the LGBT community, in the time between their abduction and their flight from Chechnya decided to help the Islamic militant Borchashvili, seems unlikely.

At the same time, a report in the case file states there has been no information about Borchashvili since 2015. He had been declared dead several times as a result of special operations. Therefore the mention of his name could have simply been a way of accusing the brothers of aiding and abetting participation in an illegal armed group.

The brothers' confessions state that, on learning of Borchashvili's death in October 2020, they became frightened and, in an effort to avoid facing criminal charges, announced their homosexual orientation and asked the LGBT network for help in leaving Russia.

This version of events advocated by the investigators seems untenable since the brothers turned for assistance to the LGBT network and spoke publicly about their abduction and torture before they had been charged. Similarly, in the context of Chechen traditional culture, it seems doubtful the young men would declare themselves to be gay when they were not.

For these reasons we consider the criminal prosecution of Isaev and Magamadov to be a continuation of their persecution for public criticism of the regime on the Internet.

In addition, the brothers' affiliation with the LGBT community appears to be an additional motive for the prosecution. Discrimination against members of the LGBT community has become one of the main policies of the current Chechen leadership and has a widespread and brutal nature, both in Russia and beyond its borders, and includes abductions, assassination attempts, and killings.

More information about the case of Isaev and Magomadov and our reasons for recognising them as political prisoners is available on the website of the Memorial Human Rights Centre.

Recognition of an individual as a political prisoner does not imply Memorial Human Rights Centre agrees with, or approves of, their views, statements, or actions.

- How you can help

You can support all political prisoners by donating to the Fund to Support Political Prisoners of the Union of Solidarity with Political Prisoners via PayPal, using the e-wallet at helppoliticalprisoners@gmail.com.